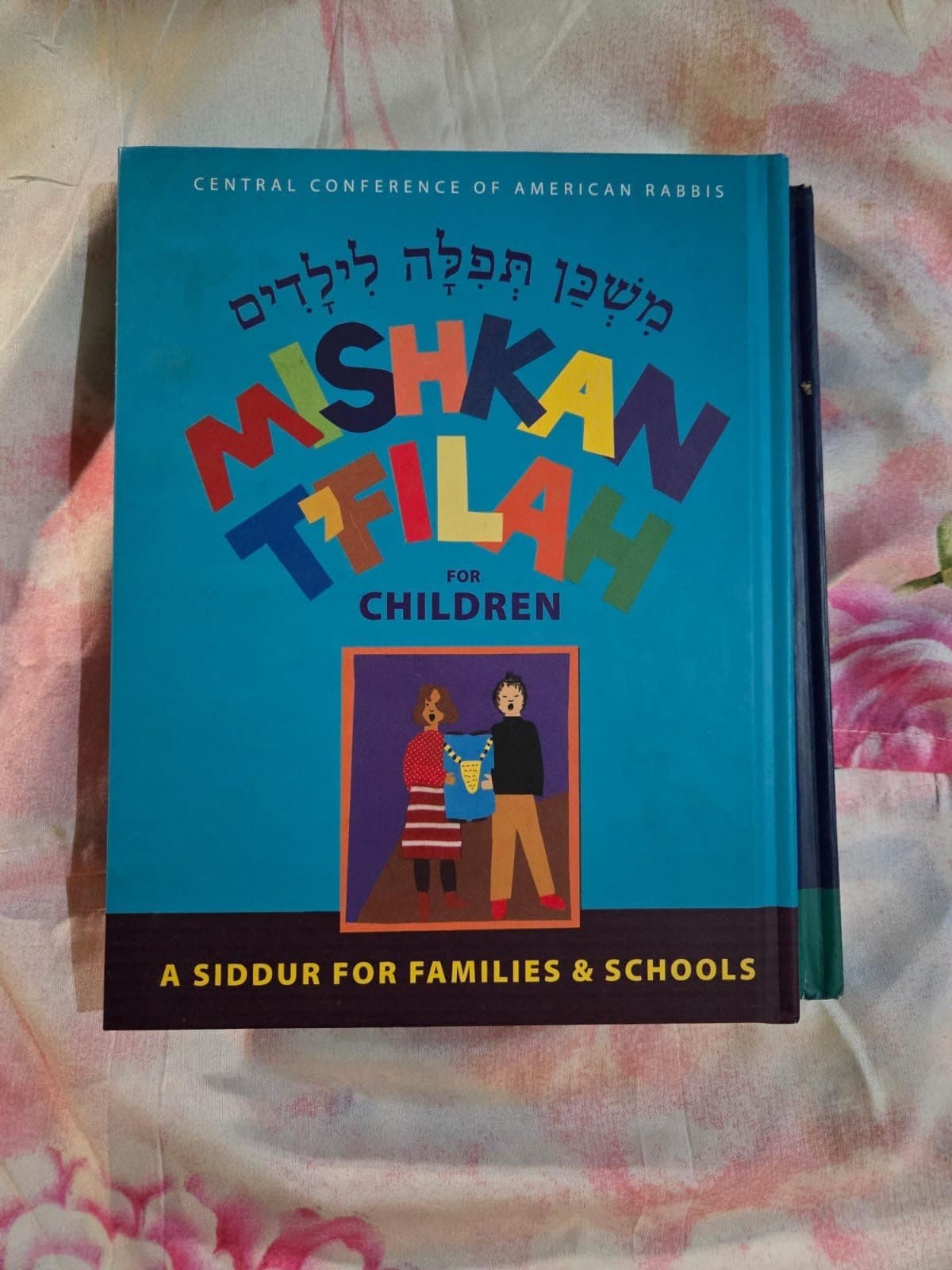

Two hundred thirty-nine faces joined my synagogue after October 7th, 2023. The adults and teenagers sat on our benches, and the children rested where their peers usually stand for Junior Choir. The youngest babies—the ones with soul-wrenching cries and powerful shouts—had car seats and pacifiers. Each mystery congregant had their own siddur, their own Mishkan T’Filah. Some mystery congregants had a different siddur: Mishkan T’Filah for Children: A Siddur for Families and Schools. It is only 30 pages with a bright blue cover and colorful illustrations.

For two decades, the Mishkan T’Filah: A Reform Siddur has been the official siddur of the Reform movement, guiding Reform Jews through their prayers. My Judaism comes from years of scouring the English parts of the massive prayer book during long, boring services for entertainment and wisdom. I consumed quotes and poems from generations of spiritual leaders, including Yehudah Amichai’s “Don’t stop after beating the swords into plowshares, don’t stop! Go on beating and make musical instruments out of them,” and Ahad Ha’am’s “More than the Jewish people have kept Shabbat, Shabbat has kept the Jewish people.”

Amichai taught me Jewish universalism: everyone is created by one G-d, so we are all equal. He taught me to value peace and to feel the tragedy of war in my soul. Ha’am taught me Jewish particularism: Jews have a unique relationship with G-d and unique responsibilities. My younger self primarily connected to Judaism through our peoplehood, but Ha’am’s words taught me to respect Jewish ritual and Jewish law because they allowed peoplehood to flourish. Later in life, when I grappled with my place in the world, I looked toward Judaism for answers. The teachings of Jewish thinkers like Rabbi Lord Jonathon Sacks helped me find it, but one of the reasons I connected with his books so much was because he referenced concepts I learned from the siddur I loved.

In 2013, the Central Conference of American Rabbis released a kid’s version.

I found it stupid. Why would anyone create a kid’s version and keep children from exploring freely? It’s like teaching someone to cook without letting them touch the oven or knives, and then wondering why they can’t cook for themselves in adulthood. In my eyes, the siddur diluted the concepts its predecessor taught me to love. I couldn’t find meaning or pray or do anything except stare at the childish pictures.

My Mishkan T’Filah is 700 pages. Each page has transliteration on the left, Hebrew on the right, and English beneath. It guides me. I see it every morning. I have a different compact all-Hebrew siddur I leave in my car, but Mishkan T’Filah, with its endless snippets of wisdom and crisp navy blue cover, is close to my heart.

Mishkan T’Filah for Children always struck me as childish, meant for babies.

Something changed when those new faces joined my synagogue. I changed. Because they weren’t two hundred and thirty-nine faces. They were two hundred and thirty-nine hostage posters with white text on a red background. In front of the poster of the youngest child, I saw the pacifier, the car seat, and the copy of Mishkan T’Filah for Children, and I thought, “Kfir Bibas can’t read it yet.”

Would he ever read it? Would he ever sit in a car seat again? Would he ever open the bright blue cover?

When Kfir Bibas’s poster joined my synagogue, he was nine months old. He would only ever exist inside those beige walls and majestic columns as a hostage poster, a car seat, and a bright blue book. I looked to my own Mishkan T’Filah for answers, but I only saw bright blue.

One Sunday morning, surrounded by the sweet sixth graders I taught at Sunday school, I wondered why no one was using the Mishkan T’filah for Children anymore. Not even the first graders. Then, I realized we probably didn’t own enough copies for both our children in sanctuary and our children in Gaza. When I said the “Sh’ma,” a declaration of monotheism and peoplehood, I recalled learning the words at age six. I saw Kfir’s face, and I prayed that he, too, would one day grow old enough to say “Sh’ma Yisrael.”

Since Hamas attacked the State of Israel on the sacred, joyous holiday of Simchat Torah, I rarely pray for myself or those around me. I don’t think it’s logical, but how can I? How can I, when those innocents stolen from their homes need all the strength G-d can give them?

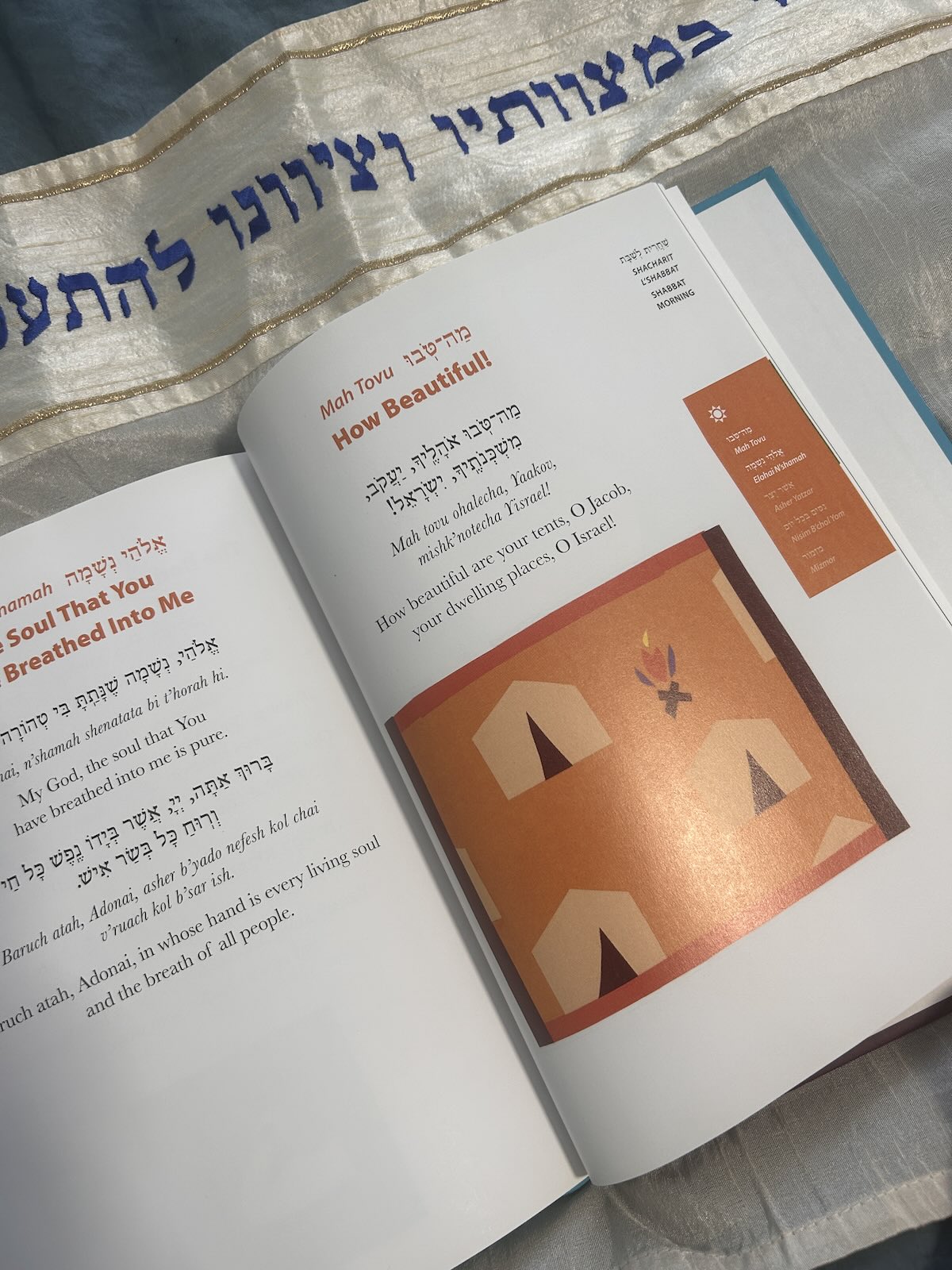

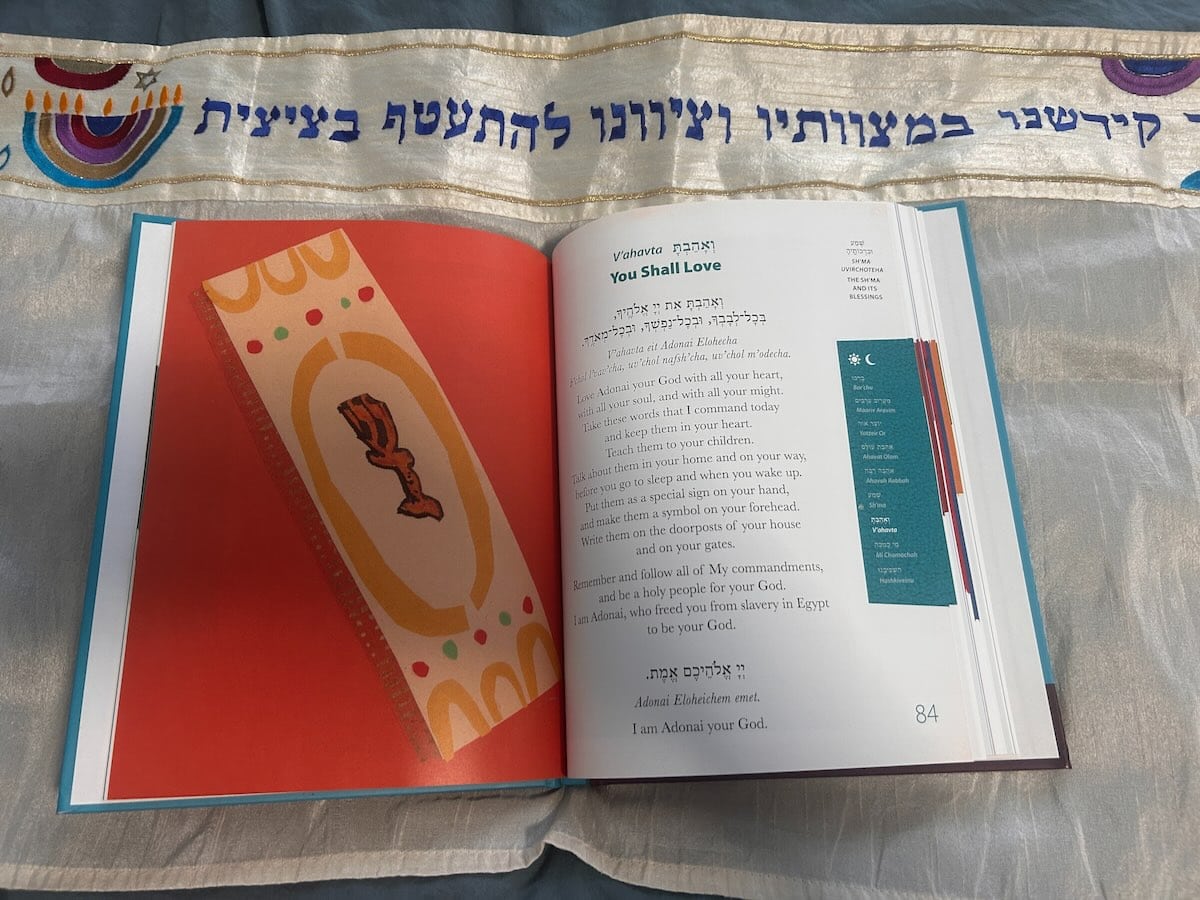

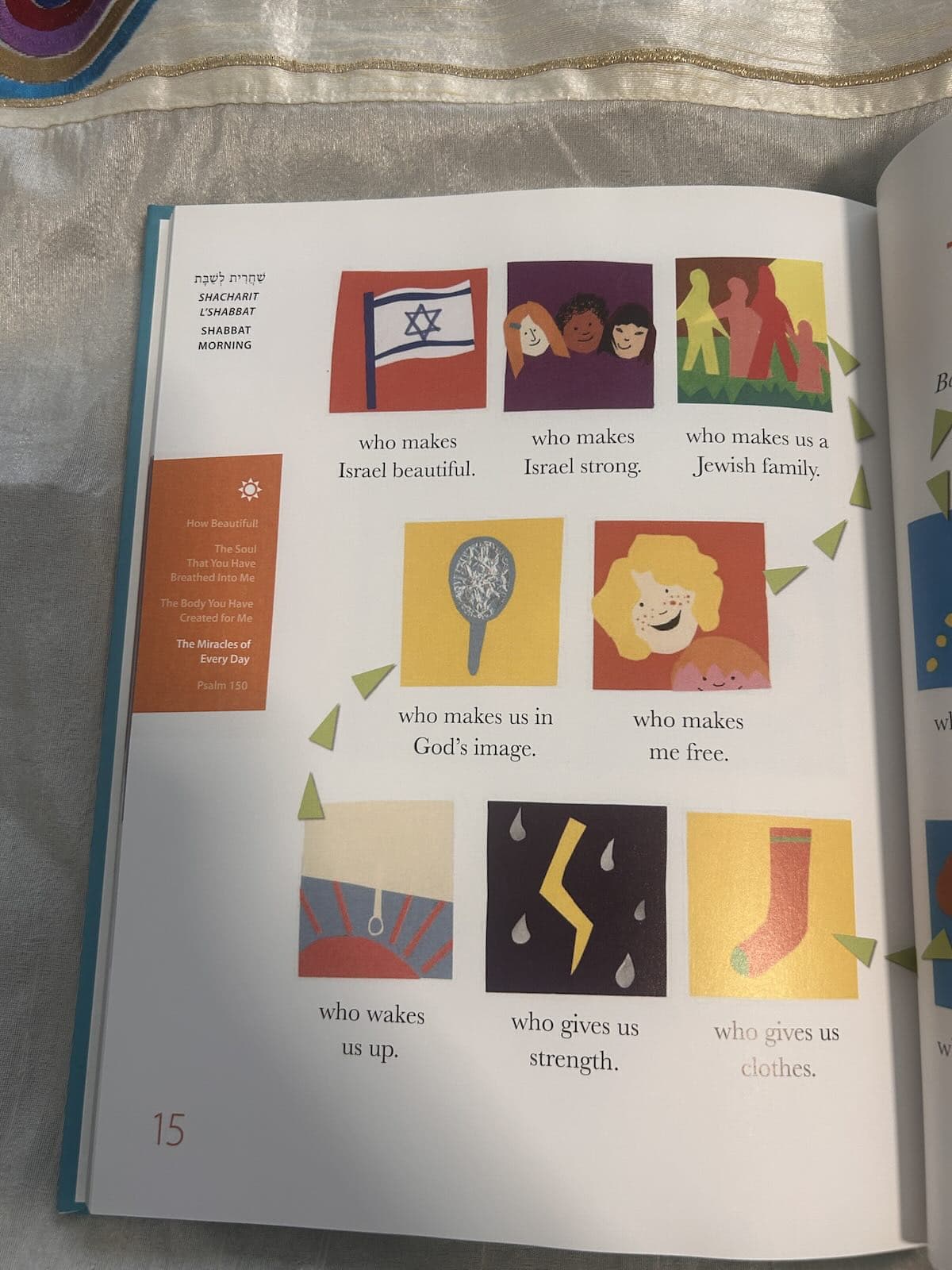

Since October 7th, I haven’t known what to say, so I listen. I listen and I sing alongside my adorable Jewish students. I sing the prayer for waking up, “Modeh Ani,” and I pray those new congregants are saying it, too. I thank G-d for creating our beautiful world with “Yotzeir Or,” but I struggle to call it beautiful. When I praise G-d for loving the Jewish people and giving us Torah with “Ahavah Rabbah,” I am reminded what an incredible hard-won gift my Jewishness is. “Nisim B’chol Yom,” praising G-d for daily miracles, is supposed to be my favorite part of the morning service. Even when everything collapses around me, I should love thanking G-d for the ability to stand, to see, to speak, to be a Jew.

Just like every day since October 7th, I grapple with one particular daily miracle. It consumes me, burns me and warms me, restarts my suppressed grief and repressed hope.

| Baruch atah Adonai, | בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יהוה |

|---|---|

| Eloheinu Melech haolam | אֱלהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעלָם |

| matir asurim. | מַתִּיר אֲסוּרִים |

Blessed are you, the Lord our G-d, Sovereign of the universe, who frees the captive.

Once, I hated Mishkan T’Filah for Children because I couldn’t pray from it. Then, I prayed that it might represent the truth. I prayed we lived in a world where Jewish children would be afforded childish picture books.

Last week, I learned we didn’t live in that world. I learned Kfir Bibas would never read the Mishkan T’Filah for Children because he returned to Israel in a coffin. Murdered before his first birthday by terrorists.

I don’t know what that book means to me anymore. I don’t know if I look at the bright blue cover and see hope for the future, betrayal by an apathetic world, a tragedy that can be turned poetic, a crime worthy of punishment, or cruelty beyond words. A world where Jewish children like Kfir are not afforded the right to childhood—aren’t afforded a pacifier, a car seat, and a siddur—isn’t a world I can accept.

I don’t know what the Mishkan T’Filah for Children means, but I know by the fact I question, by the fact I grieve, by the fact I grapple with it every day, I have completed the task Ha’am and Amichai set out for me. They taught me to love the particular and the universal, to care for my people and all people. Those two ideas sometimes seem at odds, but their contrast is their strength. What is more Jewish than being Yisrael, one who wrestles with G-d?

Join the conversation!